Available on this page as free downloads by clicking their cover pictures

Play With Knives: Four

Play With Knives: Three

Play With Knives

Play With Knives: Two

Truth in Discourse: Observations by Montaigne

Aucassin and Nicolette

Gugemer

Lanval

Guildeluec and Guilliadon (a romance known as Eliduc)

The Cuckold and the Vampires: an essay on some aspects of conservative political

manipulation of art and literature, including the experimental, and the conservatives' creation of conflict.

The Ash Tree

Honeysuckle

Bisclavret (Werewolf)

The Beauty and the Beast

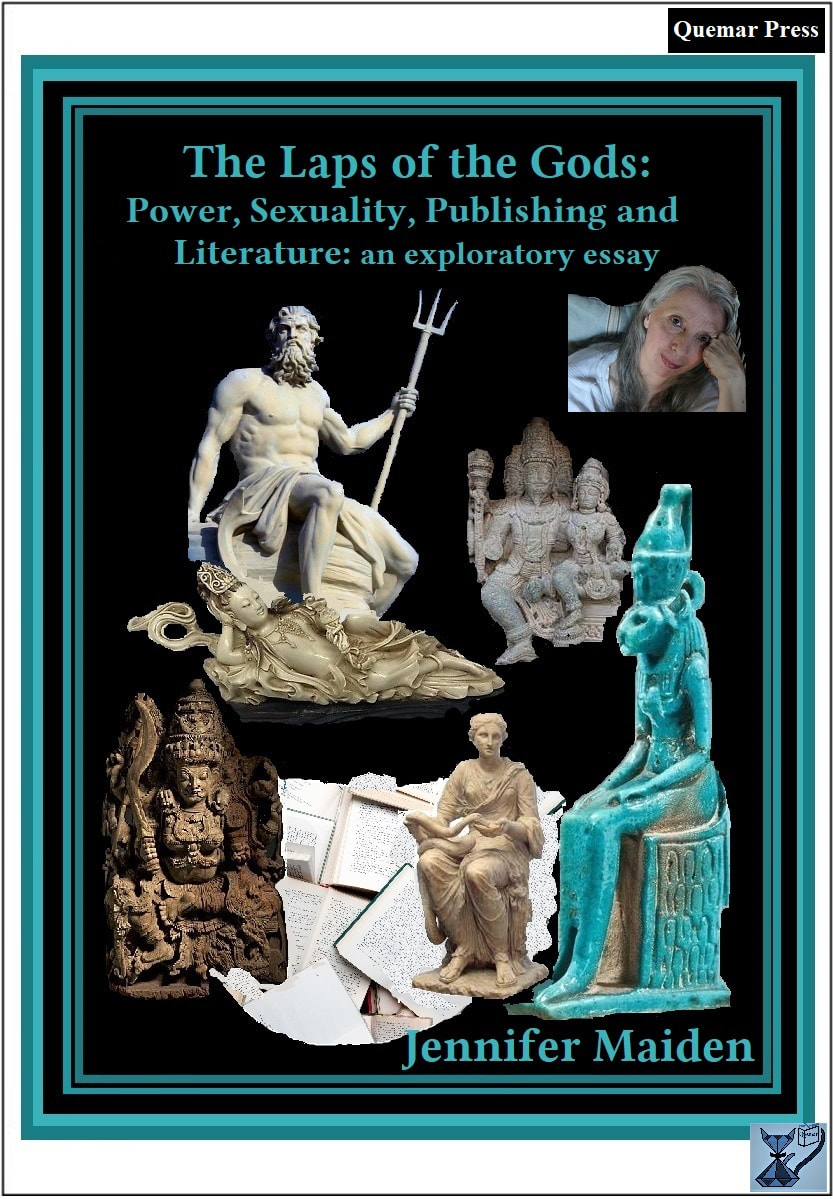

The Laps of the Gods: Power, Sexuality, Publishing and Literature: an exploratory essay

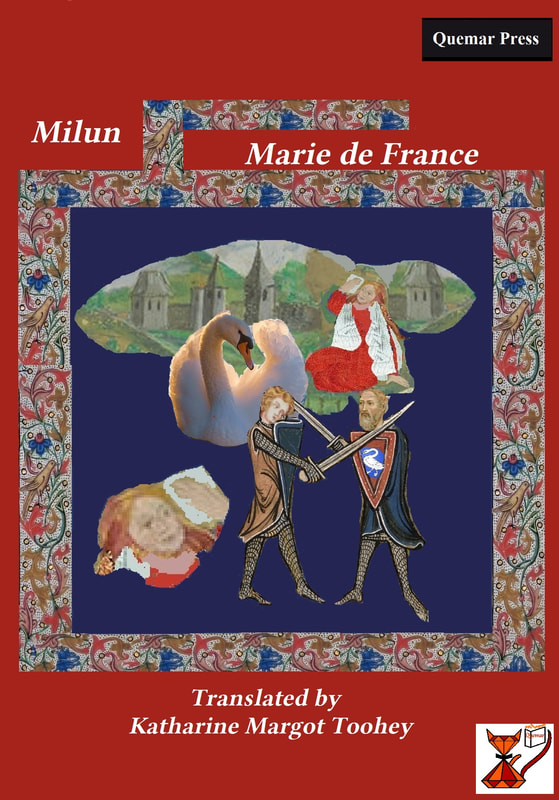

Milun

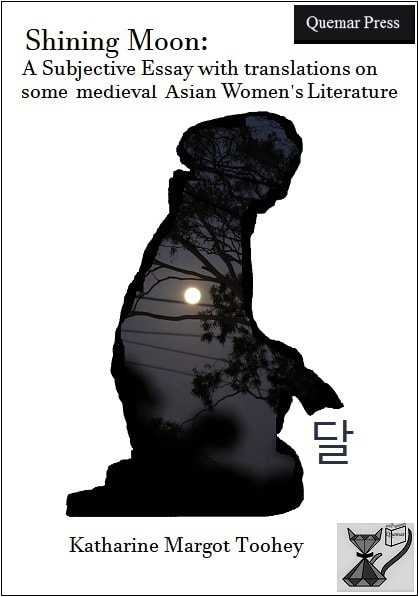

Shining Moon: A Subjective Essay with translations on some medieval Asian Women's Literature

Play With Knives: Four: George and Clare, the Baby and the Bikies, Jennifer Maiden's novel in prose and verse is available here, as a free download, by clicking on the cover picture above.

Preface

Play With Knives: Four: George and Clare, the Baby and the Bikies juxtaposes prose and verse, combining them and illuminating the thriller in a continuous pace and pattern - but as well as being a 'thriller' Play With Knives: Four is something wild and undefinable - glinting in the dark like an animal spirit or a quantum diamond.

Through verse, in the heatwave wind on backsteps, the heroes Clare and George are asked to visit a fifteen year old Indigenous boy incarcerated in a Western Suburbs Correctional Centre. In prose, George promises to find a missing baby, while watching her dog still perform tricks for her. Through verse, in the winter's 'spinning stars', the heroes learn why a drug and telecommunications criminal organiser is concerned with diamonds that could be used for quantum computing. At night, In prose, they attempt to rescue the missing baby from the criminals in an actual cave in the N.S.W. Blue Mountains named after the god Baal. In verse, the pregnant hero Clare goes into labour in an early spring of 'shivering wattle'.

The third person verse presents and facilitates mysterious true-to-life processes within the plot, such as spontaneous beauty, coincidence or serendipity. In the plot Clare experiences an empathetic dream-vision about Jimmy, the boy at the Correctional Centre, and an apple half from an anti-miscarriage spell turns into an apple plant, when it might not. Another aspect of the verse is the explicit love imagery between George and Clare, which is always in-keeping with the verse's encompassing aesthetic quality. The first person prose is a force for incarnate description and present action.

On another level, nothing in the novel, and neither Clare nor George, are compartmentalised in any way. As a child, the female hero, Clare murdered her siblings and feels she can only survive by acknowledging her murders and not being forgiven, especially not by the hero George, her former Probation officer. That everything stays connected is vital to them. Anything that happens in the verse shades the prose, and the two forms blend for the reader, incarnating the verse and expanding the prose, creating characters who wish to be complete in humanity, and also creating an unfragmented, unexpected thriller - or a work which again escapes all genres.

Katharine Margot Toohey

QUEMAR PRESS

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Preface

Play With Knives: Four: George and Clare, the Baby and the Bikies juxtaposes prose and verse, combining them and illuminating the thriller in a continuous pace and pattern - but as well as being a 'thriller' Play With Knives: Four is something wild and undefinable - glinting in the dark like an animal spirit or a quantum diamond.

Through verse, in the heatwave wind on backsteps, the heroes Clare and George are asked to visit a fifteen year old Indigenous boy incarcerated in a Western Suburbs Correctional Centre. In prose, George promises to find a missing baby, while watching her dog still perform tricks for her. Through verse, in the winter's 'spinning stars', the heroes learn why a drug and telecommunications criminal organiser is concerned with diamonds that could be used for quantum computing. At night, In prose, they attempt to rescue the missing baby from the criminals in an actual cave in the N.S.W. Blue Mountains named after the god Baal. In verse, the pregnant hero Clare goes into labour in an early spring of 'shivering wattle'.

The third person verse presents and facilitates mysterious true-to-life processes within the plot, such as spontaneous beauty, coincidence or serendipity. In the plot Clare experiences an empathetic dream-vision about Jimmy, the boy at the Correctional Centre, and an apple half from an anti-miscarriage spell turns into an apple plant, when it might not. Another aspect of the verse is the explicit love imagery between George and Clare, which is always in-keeping with the verse's encompassing aesthetic quality. The first person prose is a force for incarnate description and present action.

On another level, nothing in the novel, and neither Clare nor George, are compartmentalised in any way. As a child, the female hero, Clare murdered her siblings and feels she can only survive by acknowledging her murders and not being forgiven, especially not by the hero George, her former Probation officer. That everything stays connected is vital to them. Anything that happens in the verse shades the prose, and the two forms blend for the reader, incarnating the verse and expanding the prose, creating characters who wish to be complete in humanity, and also creating an unfragmented, unexpected thriller - or a work which again escapes all genres.

Katharine Margot Toohey

QUEMAR PRESS

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Quamar Press' exclusive new Play With Knives: Three: George and Clare and the Grey Hat Hacker, a novel in prose and verse, is available as a free download by clicking the cover image above.

PREFACE

Play With Knives: Three: George and Clare and the Grey Hat Hacker is a sequel to Maiden’s original two Play With Knives novels and those of her later poems which feature the characters George Jeffreys and Clare Collins. The ‘Grey Hat Hacker’ in the title is George’s grandson, Idris, known on the Internet as ‘Red Idris’, a daring political hacker and leaker. In another sense, the ‘Grey Hat Hacker’ is also death, ‘the blind swipe of the pruner and his knife busy about the tree of life’, as Robert Lowell has it.

George and Clare are house-sitting by the sea in Thirroul. They are in grief after they are unable to stop a round of executions by the Indonesian Government. They realise that the executions did not include a dispatch and that they had both fallen in love with one of the condemned as they tried to rescue her. Dealing with their own trauma, they spend time on their emotional and physical relationship. Maiden’s aptitude for explicit, relational love scenes is at its height here (if the reader is uncomfortable with detailed erotic depictions, they can avoid them by skipping the first verse section, chapters one and two).

Later, Idris takes refuge with George and Clare because he is being targeted by political assassins. Clare’s friend Sophie (a French woman who was saved, with her baby, by Clare in France) is now Idris’ girlfriend. She and Florence, her now seven year old daughter, come to stay with them. Sophie works with Idris to piece together ‘Frankenphone, The Unhackable Hacker’, allowing them to learn when the attack on Idris will be - information which is encrypted in Quantum in Europe. George and Clare plan to smuggle Idris to safety, and unexpected events follow.

As with the Quemar Press editions of Play With Knives and Play With Knives: Two: Complicity, Quemar asked the author to create sketches for the cover. Maiden also arranged these into a black and white collage.

The Grey Hat Hacker is exclusive to Quemar Press and does not have a print edition. Quemar Press, however, is grateful to Maiden’s print publisher, Giramondo, for its support for this project, even though Giramondo felt that the Play With Knives books did not fit into its own publishing timetable.

In Play with Knives: Three: George and Clare and the Grey Hat Hacker, Maiden glides back and forth between third person verse and first person prose, enjoying the advantages of both forms together. This also allows the forms to blend into each other, bringing illuminated lyricism to the prose and energised narrative to the verse.

Katharine Margot Toohey

QUEMAR PRESS

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

PREFACE

Play With Knives: Three: George and Clare and the Grey Hat Hacker is a sequel to Maiden’s original two Play With Knives novels and those of her later poems which feature the characters George Jeffreys and Clare Collins. The ‘Grey Hat Hacker’ in the title is George’s grandson, Idris, known on the Internet as ‘Red Idris’, a daring political hacker and leaker. In another sense, the ‘Grey Hat Hacker’ is also death, ‘the blind swipe of the pruner and his knife busy about the tree of life’, as Robert Lowell has it.

George and Clare are house-sitting by the sea in Thirroul. They are in grief after they are unable to stop a round of executions by the Indonesian Government. They realise that the executions did not include a dispatch and that they had both fallen in love with one of the condemned as they tried to rescue her. Dealing with their own trauma, they spend time on their emotional and physical relationship. Maiden’s aptitude for explicit, relational love scenes is at its height here (if the reader is uncomfortable with detailed erotic depictions, they can avoid them by skipping the first verse section, chapters one and two).

Later, Idris takes refuge with George and Clare because he is being targeted by political assassins. Clare’s friend Sophie (a French woman who was saved, with her baby, by Clare in France) is now Idris’ girlfriend. She and Florence, her now seven year old daughter, come to stay with them. Sophie works with Idris to piece together ‘Frankenphone, The Unhackable Hacker’, allowing them to learn when the attack on Idris will be - information which is encrypted in Quantum in Europe. George and Clare plan to smuggle Idris to safety, and unexpected events follow.

As with the Quemar Press editions of Play With Knives and Play With Knives: Two: Complicity, Quemar asked the author to create sketches for the cover. Maiden also arranged these into a black and white collage.

The Grey Hat Hacker is exclusive to Quemar Press and does not have a print edition. Quemar Press, however, is grateful to Maiden’s print publisher, Giramondo, for its support for this project, even though Giramondo felt that the Play With Knives books did not fit into its own publishing timetable.

In Play with Knives: Three: George and Clare and the Grey Hat Hacker, Maiden glides back and forth between third person verse and first person prose, enjoying the advantages of both forms together. This also allows the forms to blend into each other, bringing illuminated lyricism to the prose and energised narrative to the verse.

Katharine Margot Toohey

QUEMAR PRESS

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The Quemar Press edition of Jennifer Maiden's first Play With Knives novel is available here as a free download by clicking the above cover image.

PREFACE

Quemar’s edition of Play With Knives was created in close collaboration with its author, Jennifer Maiden, to preserve the original novel’s multifaceted plot, imagery and characterisation. In light of this, the text of the new edition is thoroughly revised, but focuses on expanding and clarifying narrative and diction.

A new edition of Play With Knives may be of particular interest now, as the original beautiful and striking, but insufficiently distributed, novel led to the George and Clare poems in Maiden’s current prize winning Giramondo collections. The poems, in turn, illuminate those protagonists in Play With Knives.

Also in the up-dated edition, any social or cultural aspects that could be misinterpreted by a current readership are clarified, unless necessary to illustrate complex historical or social attitudes. The phrase ‘a touch of the tar’, for example, is kept to show one character’s view of Australian indigenous heritage in the 1970s.

This edition also features a new cover sketched, at Quemar’s request, by Jennifer Maiden after she discussed her reservations about the cover of the original Allen&Unwin addition (a photo collage which was never designed for the novel), and that of the German DTV translation. The Quemar cover shows the psychic chiaroscuro proximity between Clare and George - an element that is central to the novel and continues throughout a prose sequel and the later poems.

After the publication of Play With Knives, the prose sequel, Complicity, requested by the innovative literary editor of the first edition of Play With Knives, was rejected by all publishers, but the unpublished, unedited manuscript became the object of great advocacy and also, predictably, great opposition. Because of this, it was the subject of an article in Australian Book Review, in which John Hanrahan reviewed the manuscript, and described the situation around it as Gulliver being attacked by Lilliputians. Quemar intends to publish Complicity as their next Jennifer Maiden novel online, and will be proud to be its first publisher.

Play With Knives, however, was written in the early 1980s, when its author was in her early thirties. Due to its discussion of violence, and the way it never becomes one particular genre (rather it remains as many different genres, intactly and simultaneously), publishers would not publish the work for almost eight years, until Allen&Unwin published an edited version in 1990. The manuscript itself was much larger, and Maiden has discussed how the editing took place under time constraints, as the literary editor who was supporting it was being replaced by a more conservative one. Even in the abridged form, the novel had many admirers, such as Dorothy Porter, Lyn Hughes, John Frow, and Stephen Knight. Judith Rodriguez wrote, ‘I can’t remember when a novel has so chilled and compelled me’, whilst, in the Telegraph, Maria Preraur concluded that it was ‘worthy of an Alfred Hitchcock’. As well as being worthy of Hitchcock, Quemar Press believes it is worthy of Clarence Darrow’s speech at the Leopold and Loeb trial, in which he argued that the only way to achieve remorse was by survival.

Katharine Margot Toohey

QUEMAR PRESS

The Jennifer Maiden poetry collections that include Clare and George are available from Quemar Press.

Many of her early Clare and George poems are also available from Bloodaxe Books in her Intimate Geography: Selected Poems 1991-2010: http://www.bloodaxebooks.com/ecs/category/jennifer-maiden

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The first publication of Jennifer Maiden's novel Play With Knives: Two: Complicity is available from Quemar Press as a free download by clicking the cover image above.

PREFACE

This is the first publication of Jennifer Maiden’s Play With Knives: Two: Complicity. She wrote it in 1990-1991, after Play With Knives’ original editor, Kathleen Fallon, requested a sequel. Initially, Maiden planned it as a ‘dramatised essay’ - perhaps in the sense Tolstoy had regarded War and Peace as one (he saw Anna Karenina as his first novel). Like War and Peace, PWK: Two: Complicity is, in the first instance, a love story.

Its explicit love scenes are unusual because they are entirely relational and not fetishistic, in contrast to contemporary conservative erotic novels, such as Fifty Shades. In all senses, not just sexual, PWK: Two: Complicity may be the most anti-fetishistic novel ever written.

Radical humanisation through subjectification is central to the plot. For example, the female hero, Clare, is especially objectified after killing her step siblings as a child, and their deaths have objectified them for her. Processes throughout the novel work to solve this.

As in Maiden’s later poems, Play With Knives: Two: Complicity also uses thriller and adventure plot elements to analyse politics and illustrate physical and metaphysical growth of character. The first American Gulf War is literally happening in the background (Maiden wrote her long Gulf War Sequence of poems, now available from Bloodaxe, in the same years).

Some of the political aspects seem prophetic in a contemporary context. At one stage, for example, a mercenary states that the war ‘will turn the world into tribes again’, George is hit by a ricocheted police bullet in Sydney, there is a ‘False Flag’ gunman on the loose, and powerful pharmaceutical companies have sinister connections.

The Quemar Press edition is revised and corrected by Jennifer Maiden, while retaining the original plot and political references. Quemar also agrees with the author’s decision to retain most of what she refers to as ‘self-modifying grammatical clusters’, in which several linguistic features - usually adjectives or nouns - support, contradict and qualify each other. As with Play With Knives, Quemar Press requested that she draw the illustration for the cover.

Maiden’s manuscript has a controversial history. Whilst it was praised by many of Australia’s finest critics, it was rejected by all approached publishers and attacked by some other literary figures.

Overton believed there is a window of political acceptability, which shifts to the right or left depending on social forces. Maiden’s prize-winning Giramondo poetry has not been a retreat to replace her novels. On the contrary, Quemar Press believes the success of her poetry has moved the Overton Window to the left and given Play With Knives: Two: Complicity the possibility of a new contemporary audience.

Katharine Margot Toohey

QUEMAR PRESS

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Excerpt from Australian Book Review, June no. 151 1993: (p. 21-22):

Where you go, I’ll follow

So writes John Hanrahan [1939-1997] to Jennifer Maiden of her novel ‘Complicity’. John Hanrahan… [was] an experienced author, critic and ‘publisher’s reader’, regularly called on to report on manuscripts to assess whether they should be published.

Dear Jennifer Maiden,

I know it is unusual for a minor writer to publish an open letter to an author about a manuscript of an unpublished novel. I have been informed that your novel, ‘Complicity’, has caused debate among publishers, writers, and publishers’ readers.

Though I was offered some correspondence written by people who are fighting to have you novel published, I have refrained from reading these letters, and I know little of the Gulliver’s travels of the manuscript or of the reasons why, after journeys of over a year, the manuscript has not yet been accepted by a publisher.

In agreeing to write ‘a publisher’s report’, I did so before I had read the novel, on the understanding I would write a response that was as honest as I could manage, even if that report turned out to be negative.

I am happy to tell you, and publishers, that I think this book is publishable. And should be published. You carry on with the main characters from Play with Knives. The narrator is again welfare worker George Jeffreys, descendant of the seventeenth-century judge, a famous baron who organised executions with the zeal of a chicken farmer. ‘Complicity’ develops further George’s relationship with Clare, whom he had counselled many years ago when she was in jail after murdering her two stepsisters and her stepbrother when she was nine years old.

‘Complicity’ often re-visits these crimes, as it re-visits more glancingly another set of particularly violent killings. In ‘Complicity’, murder goes hounding the users of benzodiazepines in the western suburbs of Sydney where the outsiders are blessed with the sacrament of addiction by doctors and drug companies.

The novel is mined with the images and realities of violence: the Gulf War, San Salvador, a riot outside the drug company, references to Anne Frank, a verity of guns, boxing, the IRA, Tiananmen Square. Yet it is not the violence that makes this novel powerful and disturbing. The challenge and the power lie in the eerie calm and perceptiveness of how fragile is the easy distinction between ‘normality and sanity’.

The heart of the murderer is not the heart of Satan, the monster, but the heart of Everyman and Everywoman. Sexual intimacy can become a self-annihilating act of giving or an attempt to annihilate the Other. Tenderness can be a feral emotion that has been temporarily sedated. George reminds Clare of a remark by Simone Weil that moments of attention and insights of genius are not different in kind. Sometimes the same can be said of f..king and killing.

With great assurance, Jennifer, you have explored power, manipulation, control, violence as sexual foreplay, and yet written a novel that has the strength of insight, acceptance, optimism and gentleness.

This is a novel about darkness, it walks in darkness, trembles in darkness. But the images of light and of sunshine are also appropriate because they come not from Dracula special effects but from a confident awareness of the aspirations, at once grubby and soaring, of that workhorse muscle, the human heart.

So I recommend this novel, Jennifer, and I recommend it to publishers. I recommend it in the same way, and for similar reasons that I would like to imagine I would have recommended the works of Jean Rhys, Robert Lowell, Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton.

…

‘Complicity’ is disturbing in the way good novels are. It is a refreshing change from the tupperware nouvelle cuisine that is currently served up with passionless grace, particularly by male novelists.

I am grateful, Jennifer, that you have led me into the mind of the man George, who would be god and the crucified, but has a preference for being God and the crucifier. I feel so close to Clare who killed her sisters and her brother, and died herself and now fights to achieve her own resurrection. The violence comes not from Hannibal Lecter and the silence of the lambs, but from the bleating of ordinary cross-bred sheep, some of whom will sacrificial lambs and some of whom will be pronounced lambs of God. The powerful mystery of your novel lies not in separating the sheep from the goats, but the sheep from the sheep. And how much this separation depends on a lottery that society calls ‘civilisation’. Many people deserve to win the lottery of being challenged by your novel.

Sincerely,

John Hanrahan

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Truth in Discourse is a selection of observations from Michel de Montaigne's essays, translated and photo-illustrated by Katharine Margot Toohey. It is available here as a free download by clicking the cover image above.

PREFACE

Montaigne started his original collection of essays by telling the reader that his writing is in good faith. He discerned his truth from a tower in Sixteenth Century France. To have the same focus on experiencing truth from one place, all the photographs in the new photo-illustrations were taken from the same house in Western Sydney, Australia. They were photographed in 2016 and early 2017, from a winter solstice with a moon in coloured prisms to a heatwave storm in summer. This modern context seems in keeping with Montaigne. Most writers are at their height when they represent the spirit of their time, but Montaigne could be at his best when he is out of his time and not of it: free from its physical, cultural and gender preconceptions. These new translations are not concerned with temporal, literal accuracy, but accuracy in sense. For example, the conjunctions are replaced often with commas, to show that his writing is a quick, continuous process. In the photo-illustrations, truth is a light source that interacts with elements around it, mirroring truth in the text, whether it is showing that death can be fortunate and valiant, that deformity cannot exist because all divine designs cannot be known, that virtue is an active process and goodness is passive, and ultimately, that truth itself is the only link men have to one another.

Katharine Margot Toohey

QUEMAR PRESS

PREFACE

Montaigne started his original collection of essays by telling the reader that his writing is in good faith. He discerned his truth from a tower in Sixteenth Century France. To have the same focus on experiencing truth from one place, all the photographs in the new photo-illustrations were taken from the same house in Western Sydney, Australia. They were photographed in 2016 and early 2017, from a winter solstice with a moon in coloured prisms to a heatwave storm in summer. This modern context seems in keeping with Montaigne. Most writers are at their height when they represent the spirit of their time, but Montaigne could be at his best when he is out of his time and not of it: free from its physical, cultural and gender preconceptions. These new translations are not concerned with temporal, literal accuracy, but accuracy in sense. For example, the conjunctions are replaced often with commas, to show that his writing is a quick, continuous process. In the photo-illustrations, truth is a light source that interacts with elements around it, mirroring truth in the text, whether it is showing that death can be fortunate and valiant, that deformity cannot exist because all divine designs cannot be known, that virtue is an active process and goodness is passive, and ultimately, that truth itself is the only link men have to one another.

Katharine Margot Toohey

QUEMAR PRESS

Photograph from Truth in Discourse: Observations by Montaigne

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

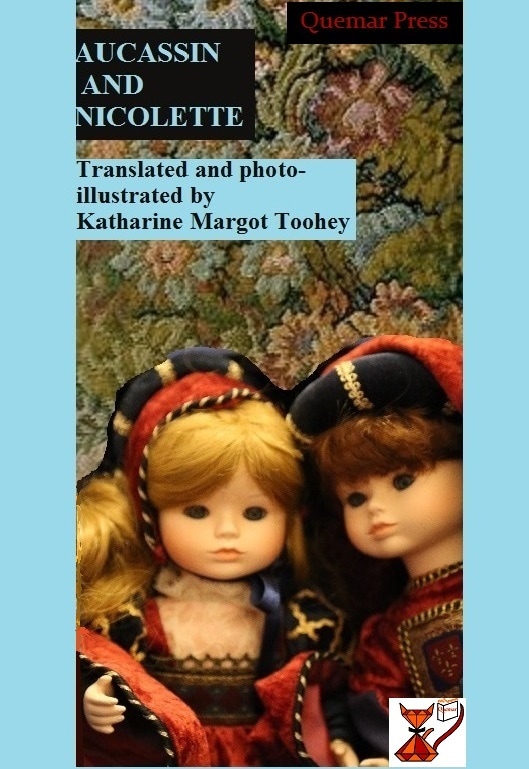

The complete Medieval French Chantefable, Aucassin et Nicolette, translated and photo-illustrated by Katharine Margot Toohey, is available as a free download by clicking on the cover picture above.

Preface

Aucassin and Nicolette is a medieval French 'chantefable' (a song-fable), written by an anonymous author. It juxtaposes and interconnects prose story and mnemonic song to create a multifaceted courtly love story.

The songs in this new translation closely reflect and try to retain the effect of the original rhyme patterns, especially the striking rhyme on the last syllable of every line, while also trying to stay close to the meaning of the diction. While keeping the text's vibrant pace, this also seems to be an essential aspect of the text's characterisation. In light of this, aspects lost in other translations may be illuminated here. It is a part of this translation, for example, that - disguised as a minstrel boy - the heroine ends the lines of her song with the same '-or' rhyme the hero used earlier towards her.

Quemar's translation is also creative, not focused on mirroring Medieval French culture. Some temporal aspects of Medieval Literature are adapted for cultural reasons, including some sections with comic hyperbole about violence that could be read literally by a modern audience.

Aucassin and Nicolette often seems to be underestimated by being seen as a work of satire, something reflected in its translations. In the text itself, however, the titular heroine, Nicolette, is seriously working out the best way she can survive a kingdom whose men want to 'burn her in a fire', to destroy her and cause fear, and the hero Aucassin is honestly fearful about going into battle because 'he might strike' another man or be struck. When he is taken prisoner in battle, he straightforwardly asks God if the knights about to decapitate him are truly his deadly enemies.

In Quemar's translation, Aucassin’s and Nicolette's need to be reunited, remain alive and practise courtesy is a sincere process. Because of that, here it is the narrative's driving strength to place the focus on developing the characters’ individual humanity rather than a satire's focus on form, concepts and objectivity.

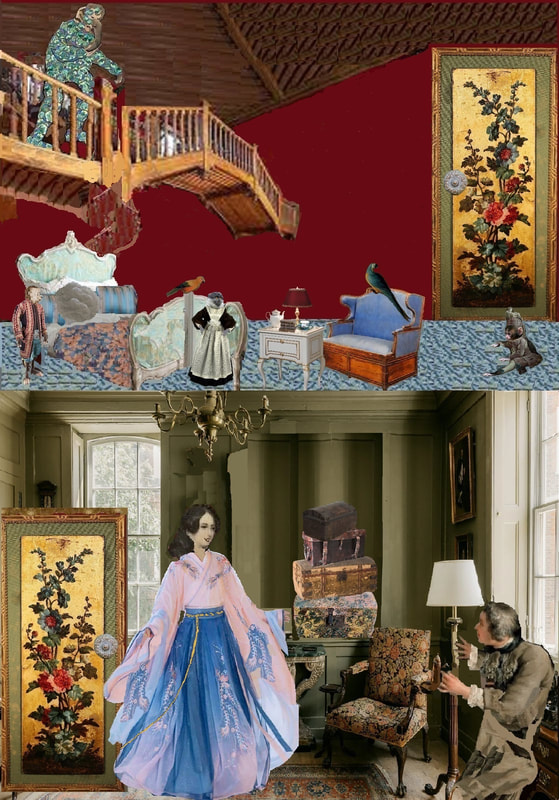

Throughout, Aucassin and Nicolette are represented by French, reproduction Medieval dolls. In the illustrations, photographs of them from 2017 combine in collages with Medieval tapestries, maps and artifacts. Whether they show Aucassin and Nicolette escaping by horse to a storm at sea or imprisoned, speaking in secret in the moonlight, the illustrations mirror the story's unusual, brilliant juxtapositions and Aucassin’s and Nicolette's ability to stay intact in every circumstance.

Quemar stresses that it is not necessary to be able to read the Medieval French original included underneath, as this English version translates all the text.

Katharine Margot Toohey

QUEMAR PRESS

Aucassin and Nicolette is a medieval French 'chantefable' (a song-fable), written by an anonymous author. It juxtaposes and interconnects prose story and mnemonic song to create a multifaceted courtly love story.

The songs in this new translation closely reflect and try to retain the effect of the original rhyme patterns, especially the striking rhyme on the last syllable of every line, while also trying to stay close to the meaning of the diction. While keeping the text's vibrant pace, this also seems to be an essential aspect of the text's characterisation. In light of this, aspects lost in other translations may be illuminated here. It is a part of this translation, for example, that - disguised as a minstrel boy - the heroine ends the lines of her song with the same '-or' rhyme the hero used earlier towards her.

Quemar's translation is also creative, not focused on mirroring Medieval French culture. Some temporal aspects of Medieval Literature are adapted for cultural reasons, including some sections with comic hyperbole about violence that could be read literally by a modern audience.

Aucassin and Nicolette often seems to be underestimated by being seen as a work of satire, something reflected in its translations. In the text itself, however, the titular heroine, Nicolette, is seriously working out the best way she can survive a kingdom whose men want to 'burn her in a fire', to destroy her and cause fear, and the hero Aucassin is honestly fearful about going into battle because 'he might strike' another man or be struck. When he is taken prisoner in battle, he straightforwardly asks God if the knights about to decapitate him are truly his deadly enemies.

In Quemar's translation, Aucassin’s and Nicolette's need to be reunited, remain alive and practise courtesy is a sincere process. Because of that, here it is the narrative's driving strength to place the focus on developing the characters’ individual humanity rather than a satire's focus on form, concepts and objectivity.

Throughout, Aucassin and Nicolette are represented by French, reproduction Medieval dolls. In the illustrations, photographs of them from 2017 combine in collages with Medieval tapestries, maps and artifacts. Whether they show Aucassin and Nicolette escaping by horse to a storm at sea or imprisoned, speaking in secret in the moonlight, the illustrations mirror the story's unusual, brilliant juxtapositions and Aucassin’s and Nicolette's ability to stay intact in every circumstance.

Quemar stresses that it is not necessary to be able to read the Medieval French original included underneath, as this English version translates all the text.

Katharine Margot Toohey

QUEMAR PRESS

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Quemar Press' new Modern English translation of Gugemer, Marie de France's Medieval French Romance, is available here as a free download by clicking on the cover below.

Quemar Press' introduction:

In this work, Marie de France states that the the text itself is a translation from a Breton Lai into Anglo-Norman French verse. Marie de France's works have been dated to a period between 1160 and 1215, leading Marie de France to be considered the earliest female French poet. In Gugemer, Marie, the storyteller herself, is a driving subjective voice, analysing the story from her own interpretations. Here, where storyteller is individual and interpreter, there seems a profound, unusual sense of this Romance's history, continuity and veracity. For her, some elements may be unsure, a time-frame may seem to her to be a certain length, while she can speak of other elements without uncertainty, as known, sure aspects of the story. Her original text is included in this work, with Quemar's Modern English translation

A constant element through the original text is a traditional four stress rhyme scheme, something which let the words be set to music on medieval harp or guitar. This new translation tries to retain that form, to keep the text's resonant vibrancy.

In some translations of this Romance, the male hero, the Knight Gugemer, could be seen as passive or subject to fate, retribution or curse. After the Knight hunts and strikes a white, otherworldy doe, his arrow instantly rebounds, striking him. The doe speaks to say his wound will only heal if he and a lady suffer for love. These words, however, seem to set a test, one in which he and the Lady make active choices.

Throughout, they appear to cooperate with indefinable or magic elements, instead of resting passively subject to a curse, whether the elements are a shimmering prescient doe with antlers or an enigmatic ship, sailing with quick deliberation to unite the knight and Lady. In the text, he listens seriously to the doe's test. When the Lady is imprisoned and separated from him, instead of remaining captive, she escapes to the sea's shore and finds the ship, sensing it can transcend perilous situations. Ultimately, spiritual or unknown forces can be benign here. Quemar's translation focuses on the characters, endeavoring to maintain the text's human, humane focus.

This is a space where redemption, survival and courtly love can be achieved, in action and focused attention, venturing uncertain across sea waves, castle walls and unpredictable forests.

Katharine Margot Toohey

Quemar Press

In this work, Marie de France states that the the text itself is a translation from a Breton Lai into Anglo-Norman French verse. Marie de France's works have been dated to a period between 1160 and 1215, leading Marie de France to be considered the earliest female French poet. In Gugemer, Marie, the storyteller herself, is a driving subjective voice, analysing the story from her own interpretations. Here, where storyteller is individual and interpreter, there seems a profound, unusual sense of this Romance's history, continuity and veracity. For her, some elements may be unsure, a time-frame may seem to her to be a certain length, while she can speak of other elements without uncertainty, as known, sure aspects of the story. Her original text is included in this work, with Quemar's Modern English translation

A constant element through the original text is a traditional four stress rhyme scheme, something which let the words be set to music on medieval harp or guitar. This new translation tries to retain that form, to keep the text's resonant vibrancy.

In some translations of this Romance, the male hero, the Knight Gugemer, could be seen as passive or subject to fate, retribution or curse. After the Knight hunts and strikes a white, otherworldy doe, his arrow instantly rebounds, striking him. The doe speaks to say his wound will only heal if he and a lady suffer for love. These words, however, seem to set a test, one in which he and the Lady make active choices.

Throughout, they appear to cooperate with indefinable or magic elements, instead of resting passively subject to a curse, whether the elements are a shimmering prescient doe with antlers or an enigmatic ship, sailing with quick deliberation to unite the knight and Lady. In the text, he listens seriously to the doe's test. When the Lady is imprisoned and separated from him, instead of remaining captive, she escapes to the sea's shore and finds the ship, sensing it can transcend perilous situations. Ultimately, spiritual or unknown forces can be benign here. Quemar's translation focuses on the characters, endeavoring to maintain the text's human, humane focus.

This is a space where redemption, survival and courtly love can be achieved, in action and focused attention, venturing uncertain across sea waves, castle walls and unpredictable forests.

Katharine Margot Toohey

Quemar Press

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Quemar Press' new Modern English translation of Lanval, Marie de France's Medieval French Romance, is available here as a free download by clicking on the cover below.

Quemar Press' Preface:

Marie de France's Medieval Anglo-Norman Romance, Lanval, may be seen often as a story in which a Knight, a city and all those within it are affected by an ethereal force, far-reaching, capable of the act of rescue, a force surrounding and intrinsic to a sprite-like Lady, the Ladies who serve her and the spaces around her. Some translations of the text might mirror this interpretation. In the original text, however, the Lady might not be seen as only an aspect of an enchanted process. Instead, she has active agency and distinct emotions, judges the best course of action and decides to act. She asks that the titular hero, the Knight Lanval, be brought to her when he lies in a water-meadow, dejected by the Court's injustice. In candour, she tells him that she could never appear visible before him again if he let anyone know of their affection. When her existence and her presence are the only things that can rescue him from the Court's corruption, she rides openly through the city, having decided to speak unconcealed before Lanval and the Court. Just as she is an entity distinct from elements surrounding her, Lanval is also never at one with the Court. In light of this, Quemar's new Modern English translation tries to preserve the text's focus on creating characterisation that enhances a character’s distinctness and independence from their situation.

This translation also tries to reflect the text's original speed and urgency by suggesting Marie de France's powerful four stresses to a line and her couplet rhyme-scheme. Considered the earliest female French poet, she based her late 12th Century Lais on traditional Breton Lais, and she recounts the romances speaking as a storyteller commenting within the text. Quemar's translation tries to retain her direct, humane tone.

In this Romance, instances in which injustice is prevented by public truth are as important as enchantment. Here, the female hero can stand focused and otherworldly in a corrupt Court or a Knight can renounce the Court to ride fast with her to Avalon, her living place, an enchanted orchard-island distant and fair in all senses.

Katharine Margot Toohey

Quemar Press

Marie de France's Medieval Anglo-Norman Romance, Lanval, may be seen often as a story in which a Knight, a city and all those within it are affected by an ethereal force, far-reaching, capable of the act of rescue, a force surrounding and intrinsic to a sprite-like Lady, the Ladies who serve her and the spaces around her. Some translations of the text might mirror this interpretation. In the original text, however, the Lady might not be seen as only an aspect of an enchanted process. Instead, she has active agency and distinct emotions, judges the best course of action and decides to act. She asks that the titular hero, the Knight Lanval, be brought to her when he lies in a water-meadow, dejected by the Court's injustice. In candour, she tells him that she could never appear visible before him again if he let anyone know of their affection. When her existence and her presence are the only things that can rescue him from the Court's corruption, she rides openly through the city, having decided to speak unconcealed before Lanval and the Court. Just as she is an entity distinct from elements surrounding her, Lanval is also never at one with the Court. In light of this, Quemar's new Modern English translation tries to preserve the text's focus on creating characterisation that enhances a character’s distinctness and independence from their situation.

This translation also tries to reflect the text's original speed and urgency by suggesting Marie de France's powerful four stresses to a line and her couplet rhyme-scheme. Considered the earliest female French poet, she based her late 12th Century Lais on traditional Breton Lais, and she recounts the romances speaking as a storyteller commenting within the text. Quemar's translation tries to retain her direct, humane tone.

In this Romance, instances in which injustice is prevented by public truth are as important as enchantment. Here, the female hero can stand focused and otherworldly in a corrupt Court or a Knight can renounce the Court to ride fast with her to Avalon, her living place, an enchanted orchard-island distant and fair in all senses.

Katharine Margot Toohey

Quemar Press

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

,Quemar Press' new Modern English translation of Marie de France's Guildeluec and Guilliadon ( a romance known as Eliduc) is available here as a free download by clicking on the cover below.

Quemar Press' Preface:

The Quemar Press Edition of this unusual Romance by Marie de France, has the title Guildeluec and Guilliadon - the names of its female heroes. Marie begins the story, ‘Because of both, the Lay is known/as Guildeluec and Guilliadon./Eliduc was its first name,/ but then the other title came,/ because this Lay's real adventure/ happened to the two ladies here.’ Later, however, the work came again to be known almost exclusively as Eliduc, after the male central character. Reflecting Marie’s reasoning, Quemar uses Guildeluec and Guilliadon as this Lay’s title, as the two women are ultimately the narrative’s catalysts and focus.

Quemar's new Modern English translation is presented here accompanied by the original 12th century text in Anglo-Norman French. Marie de France's translated and constructed her Lays based on stories from early Breton. To retain the narrative pace of the original, formal punctuation and capitalisation are minimised in the Modern English translation.

Often, elements of nature in the narrative have been interpreted as allegorical, mirroring other emotions, actions or aspects. In the text, however, it seems that natural elements can have power and roles independent from any metaphor. Here, a weasel can show the lady Guildeluec how to restore Guilliadon (the beloved of her husband Eliduc), by reviving its own companion weasel, instead of only mirroring Guildeluec as a resurrecting force in grief. The abilities of the lady and the weasel appear clear, incarnate, individual in problem-solving and effort. Here, the natural creature seems to be not just an allegory, but to have as much agency as the protagonist. Likewise, the two human female protagonists gain significance by having the power of observation and deliberation.

Similarly, a ship in a storm on the ocean does not only parallel the dangerous situation surrounding the Princess Guilliadon, uninformed about her betrothed’s wife and about the secrets kept from her. Here, a sea-tempest is a setting that actively causes truth to be revealed to her - by one of the ship's crew, afraid of the storm's intensity.

A chapel in immense forest is not just a signal or a metaphor for benign change, revival and spiritual realisation, but ground on which Guildeluec can choose to build her holy order as an Abbess.

Near the story's conclusion, the narrator explains 'they all made such effort/by the love of God, with beautiful faith,/so made their ending beautiful completely'. Here, effort belongs to both natural force and protagonist, whether it is a storm forcing necessary truth to be revealed, or someone actively on watch over one she resurrected. Whether in a wave-torn ship, or unfolding and enfolding forest depths, this is a story where humane survival, affection and rescue come from action and deliberation, to surpass societal concepts such as roles in relationships, marriage and rivalry. In light of this, this translation uses the active verb ‘remember’ in the last line, instead of the more passive 'should not forget'. This also empathises Marie’s point that the important thing is not just to retain this lay as an artistic work ( as has been the version in previous translations) but to remember deliberately the meaning of its words: 'The adventure, the story of the three,/ was told by ancient Bretons of courtesy./They constructed a lay to remember/this, which man should remember ever'.

Katharine Margot Toohey

Quemar Press

The Quemar Press Edition of this unusual Romance by Marie de France, has the title Guildeluec and Guilliadon - the names of its female heroes. Marie begins the story, ‘Because of both, the Lay is known/as Guildeluec and Guilliadon./Eliduc was its first name,/ but then the other title came,/ because this Lay's real adventure/ happened to the two ladies here.’ Later, however, the work came again to be known almost exclusively as Eliduc, after the male central character. Reflecting Marie’s reasoning, Quemar uses Guildeluec and Guilliadon as this Lay’s title, as the two women are ultimately the narrative’s catalysts and focus.

Quemar's new Modern English translation is presented here accompanied by the original 12th century text in Anglo-Norman French. Marie de France's translated and constructed her Lays based on stories from early Breton. To retain the narrative pace of the original, formal punctuation and capitalisation are minimised in the Modern English translation.

Often, elements of nature in the narrative have been interpreted as allegorical, mirroring other emotions, actions or aspects. In the text, however, it seems that natural elements can have power and roles independent from any metaphor. Here, a weasel can show the lady Guildeluec how to restore Guilliadon (the beloved of her husband Eliduc), by reviving its own companion weasel, instead of only mirroring Guildeluec as a resurrecting force in grief. The abilities of the lady and the weasel appear clear, incarnate, individual in problem-solving and effort. Here, the natural creature seems to be not just an allegory, but to have as much agency as the protagonist. Likewise, the two human female protagonists gain significance by having the power of observation and deliberation.

Similarly, a ship in a storm on the ocean does not only parallel the dangerous situation surrounding the Princess Guilliadon, uninformed about her betrothed’s wife and about the secrets kept from her. Here, a sea-tempest is a setting that actively causes truth to be revealed to her - by one of the ship's crew, afraid of the storm's intensity.

A chapel in immense forest is not just a signal or a metaphor for benign change, revival and spiritual realisation, but ground on which Guildeluec can choose to build her holy order as an Abbess.

Near the story's conclusion, the narrator explains 'they all made such effort/by the love of God, with beautiful faith,/so made their ending beautiful completely'. Here, effort belongs to both natural force and protagonist, whether it is a storm forcing necessary truth to be revealed, or someone actively on watch over one she resurrected. Whether in a wave-torn ship, or unfolding and enfolding forest depths, this is a story where humane survival, affection and rescue come from action and deliberation, to surpass societal concepts such as roles in relationships, marriage and rivalry. In light of this, this translation uses the active verb ‘remember’ in the last line, instead of the more passive 'should not forget'. This also empathises Marie’s point that the important thing is not just to retain this lay as an artistic work ( as has been the version in previous translations) but to remember deliberately the meaning of its words: 'The adventure, the story of the three,/ was told by ancient Bretons of courtesy./They constructed a lay to remember/this, which man should remember ever'.

Katharine Margot Toohey

Quemar Press

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Jennifer Maiden's 75-page The Cuckold and the Vampires: an essay on some aspects of conservative political manipulation of art and literature, including the experimental, and the conservatives' creation of conflict is available here as a free download by clicking on the cover below.

The Cuckold and the Vampires is Jennifer Maiden’s extraordinary over-32,700-word subjective essay on aspects of conservative political manipulation of art and literature, including the experimental, and the conservatives' creation of conflict - ranging from Medieval to Ruskin, from Pollock to contemporary Australia. Maiden has observed: ‘One purpose of the essay is to try to warn against microcosmic unwariness in a situation where overwhelming macrocosmic forces are at play…there are all sorts of twists and turns during the course of my essay. My focus is on the wider causes of damage and the nature of power in art… we will continue to try here to respect what Pinter considered mandatory and to smash the mirror of the microcosm, to try to look at the macrocosm behind it.’ The essay is immense in scope and immensely enjoyable, astute and witty.

Topics include Marquez, the CIA-created magazine Encounter, Quadrant, Paris Review, Congress for Cultural Freedom, Borges, Salusinszky, Pollock, Expressionism, Surrealism, persona, Plath, Alvarez, Operations Paperclip and Mockingbird, ‘Poetry Wars’, Rozanna and Kate Lilley, Tranter, Allende, Joan Maas, Grace Perry, Adamson, Roland Robinson, Australian Poetry Magazine, Poetry Australia, Judith Wright, Beaver, A.D.Hope, Murray, conspiracy theories, A.J.P.Taylor, Marx, Operation AEDINOSAUR, Pasternak, Nobel Prize, Pinter, Ruskin, Christine de Pizan, Demidenko, Kramer, Henderson, Kermode, Northrop Frye, Vietnam, Paterson, Lawson, Orwell, the MI in the car to Orange, Ern Malley, Border Ballads, Kipling, The Bulletin, Maiden's Indian ancestry, conservatism by copyright and pulping books, Judith Rodriguez, Drug Culture, MKUltra, Scott Morrison, Keating, Arts Policy, Copyright bodies, Rhodes, Jim Morrison, Council on Foreign Relations, Maiden's marsupial character Brookings, Dylan Thomas, Aneurin Bevan, spy thrillers, Graham Greene, Martin Johnston, Forbes, Viidikas, Peter Porter, Sophocles, Pybus, Sparkes Orr, Beauvoir, Bardot, Lawrence, Pankhursts, White, Dr. Leavis, Conrad, Henry James, Webby, Wilkes, Lascaris, Museum of Modern Art, Buttigieg, Jeffrey Epstein, Cockatoo and Naoshima Islands, Whistler, Information Research Department, Boy's Own Paper, Stephen Ward, White Helmets, Tasmania's Museum of Old and New Art, Koestler, Humboldt, Michelangelo, Sydney Review of Books, Hannah Kent, Peter Craven, Indigenous writers, Everest, Medieval Venice, Aretino, Titian, Bellini, artistic rivalry, rhythmic metrical nature of internet, Thea Astley, Uncle Tom's Cabin, Henry Kendall, Eve Kendall, Conservative Hissy Fits, Robeson, Clinton, Gaddafi, literary conflict in Dublin, Tolstoy.

Topics include Marquez, the CIA-created magazine Encounter, Quadrant, Paris Review, Congress for Cultural Freedom, Borges, Salusinszky, Pollock, Expressionism, Surrealism, persona, Plath, Alvarez, Operations Paperclip and Mockingbird, ‘Poetry Wars’, Rozanna and Kate Lilley, Tranter, Allende, Joan Maas, Grace Perry, Adamson, Roland Robinson, Australian Poetry Magazine, Poetry Australia, Judith Wright, Beaver, A.D.Hope, Murray, conspiracy theories, A.J.P.Taylor, Marx, Operation AEDINOSAUR, Pasternak, Nobel Prize, Pinter, Ruskin, Christine de Pizan, Demidenko, Kramer, Henderson, Kermode, Northrop Frye, Vietnam, Paterson, Lawson, Orwell, the MI in the car to Orange, Ern Malley, Border Ballads, Kipling, The Bulletin, Maiden's Indian ancestry, conservatism by copyright and pulping books, Judith Rodriguez, Drug Culture, MKUltra, Scott Morrison, Keating, Arts Policy, Copyright bodies, Rhodes, Jim Morrison, Council on Foreign Relations, Maiden's marsupial character Brookings, Dylan Thomas, Aneurin Bevan, spy thrillers, Graham Greene, Martin Johnston, Forbes, Viidikas, Peter Porter, Sophocles, Pybus, Sparkes Orr, Beauvoir, Bardot, Lawrence, Pankhursts, White, Dr. Leavis, Conrad, Henry James, Webby, Wilkes, Lascaris, Museum of Modern Art, Buttigieg, Jeffrey Epstein, Cockatoo and Naoshima Islands, Whistler, Information Research Department, Boy's Own Paper, Stephen Ward, White Helmets, Tasmania's Museum of Old and New Art, Koestler, Humboldt, Michelangelo, Sydney Review of Books, Hannah Kent, Peter Craven, Indigenous writers, Everest, Medieval Venice, Aretino, Titian, Bellini, artistic rivalry, rhythmic metrical nature of internet, Thea Astley, Uncle Tom's Cabin, Henry Kendall, Eve Kendall, Conservative Hissy Fits, Robeson, Clinton, Gaddafi, literary conflict in Dublin, Tolstoy.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Quemar Press' new Modern English translation of The Ash Tree, Marie de France's medieval French Romance, is available here as a free download by clicking on the cover below.

Quemar Press' Preface:

In this lai, spontaneous affection overcomes conceptual rejection. Here, the female hero does not wish suffering or punishment for a woman who abandoned her. Instead, the situation comes to a solution when both women realise the existence of the other - the ultimate remedy for them is the reality of each other. In this text, in a darkened room by night, the hero's mother can exclaim in new levels of clarity, away from all secrets: 'Beautiful friend, you are my daughter!'

Marie de France's text, in 12-century Anglo-Norman French, was based on traditional Breton Lais. Quemar's Modern English translation is juxtaposed with the original. The translation strives to maintain the original's vitality, cadence, four stresses and the effect of the rhymed final syllables. The work's illustrations are inspired by medieval artwork.

This Romance is named after the female hero, Fresne - the lady given the name of the Ash Tree, as she was resting in its branches when she was found, wrapped in a fine cloth - a cloth which would let her mother recognise her again by chance or serendipity. Her mother had given birth to her and her twin sister but feared for her own public reputation. She had slandered her neighbour's twins and fidelity by suggesting that it was not possible to give birth to twins without being promiscuous. Her mother had Fresne left at a minster, where her gentlewoman prayed and chose the Ash Tree to leave her.

'she turned and looked behind

to see an ash wide and branching

and very thick with its branches spreading,

the branches growing as four quarters.

It was planted here for shelter.

In her arms, she took the baby

and she ran to the ash tree,

set her there and left her there,

in truth to God entrusted her.'

The branching Ash protects the child from danger. She is nurtured by the Abbess who has great affection for her. All know her to be named after the tree. The Ash tree seems to act not as a talisman for her but as an element with which she is at one: an element that could signify a natural protective force steadfast through night, secrecy, danger or abandonment - something that ensured Fresne's existence.

The Ash tree is also something tangible for Fresne in the mystery surrounding her birth, as are the fine cloth and a ring left with her. She carries these possessions by her - objects that lead her mother to realise that she knows unwaveringly Fresne is her daughter.

'So she brought the ring to her

and the lady studied it there

and she recognised it clearly,

and the fine fabric close by,

and believed, knew without question

her other daughter was this young woman.'

This is a story where the woman's individuality, reality and being are powerful catalysts driving the plot, and remorse is far out-weighed by joy at having found at last the woman lost. There is a line 'What you please is forgiven'.

Katharine Margot Toohey

Quemar Press

In this lai, spontaneous affection overcomes conceptual rejection. Here, the female hero does not wish suffering or punishment for a woman who abandoned her. Instead, the situation comes to a solution when both women realise the existence of the other - the ultimate remedy for them is the reality of each other. In this text, in a darkened room by night, the hero's mother can exclaim in new levels of clarity, away from all secrets: 'Beautiful friend, you are my daughter!'

Marie de France's text, in 12-century Anglo-Norman French, was based on traditional Breton Lais. Quemar's Modern English translation is juxtaposed with the original. The translation strives to maintain the original's vitality, cadence, four stresses and the effect of the rhymed final syllables. The work's illustrations are inspired by medieval artwork.

This Romance is named after the female hero, Fresne - the lady given the name of the Ash Tree, as she was resting in its branches when she was found, wrapped in a fine cloth - a cloth which would let her mother recognise her again by chance or serendipity. Her mother had given birth to her and her twin sister but feared for her own public reputation. She had slandered her neighbour's twins and fidelity by suggesting that it was not possible to give birth to twins without being promiscuous. Her mother had Fresne left at a minster, where her gentlewoman prayed and chose the Ash Tree to leave her.

'she turned and looked behind

to see an ash wide and branching

and very thick with its branches spreading,

the branches growing as four quarters.

It was planted here for shelter.

In her arms, she took the baby

and she ran to the ash tree,

set her there and left her there,

in truth to God entrusted her.'

The branching Ash protects the child from danger. She is nurtured by the Abbess who has great affection for her. All know her to be named after the tree. The Ash tree seems to act not as a talisman for her but as an element with which she is at one: an element that could signify a natural protective force steadfast through night, secrecy, danger or abandonment - something that ensured Fresne's existence.

The Ash tree is also something tangible for Fresne in the mystery surrounding her birth, as are the fine cloth and a ring left with her. She carries these possessions by her - objects that lead her mother to realise that she knows unwaveringly Fresne is her daughter.

'So she brought the ring to her

and the lady studied it there

and she recognised it clearly,

and the fine fabric close by,

and believed, knew without question

her other daughter was this young woman.'

This is a story where the woman's individuality, reality and being are powerful catalysts driving the plot, and remorse is far out-weighed by joy at having found at last the woman lost. There is a line 'What you please is forgiven'.

Katharine Margot Toohey

Quemar Press

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Quemar Press' new Modern English translation of Honeysuckle, Marie de France's medieval French Romance, is available here as a free download by clicking on the cover below.

Quemar Press' Preface:

Marie de France's 12th-century lai, Honeysuckle (Chevrefoil), seems to re-imagine the traditional tragic Romance of Iseult and Tristan, in a chosen catalytic space - deep in a forest where the heroes interlink in communication and affection: just as, Marie writes, the honeysuckle vine of the title entwines with hazel. The forest is a sanctuary or hiding place for Tristan, exiled by the King, his uncle, for his love of Iseult, the Queen.

In Marie de France's original Anglo-Norman French text, the female protagonist is known only as 'the Queen'. Here, there is no need for her to be anything other than 'the Queen' - a title independent of her husband, the King, and something she can inhabit in this work as she acts against royal decree in endeavouring to be reunited with Tristan. In such a way, her title becomes a way of describing her self, rather than a position in a royal hierarchy.

Here, their meeting is not subject to fate, luck or chance, but happens through their own agency and ability to act - just as she steps along an alternate forest path to find him, and he carves his name on hazel in signal to her.

To mirror this fast-pace and cadence, Quemar's creative Modern English translation tries to retain the author's original four stresses to a line and driving final rhyme. While the translation is of all the original Anglo-Norman text, the original is also included for appreciation and interest, juxtaposed with the translation.

Marie de France based her work on early Breton lais and refers to historic interpretations of Iseult and Tristan's legend, as she assures that she will tell the Romance honestly, perhaps suggesting that other versions of it are fictitious. With layers of intertextuality, she begins:

'It is my wish, it is my will

to tell the Lai Honeysuckle,

to tell the truth now of this story,

why it came to be,

tale told to me through the ages

and I found in written pages,

tale of Tristan, tale of the Queen

about their love that was so fine.

For it they had such dolour.

They would die in a day together.'

The text seems to suggest that intervention is possible - a hiding place away from exile, moments of speaking together in forest depths that could lead to resolution:

'Unhindered, he spoke with her

and she said to him her pleasure.

Then she explained to him

how to reach agreement with the King:

this weighed on him heavily

- the one he sent away.'

Perhaps the lai ultimately suggests that this problem-solving would be most in keeping with the heroes' characterisation. Marie concludes by recounting that the character Tristan is the lai's author - a narrative device that gives the work new aspects of veracity and authoritative voice, and turns the lai itself into a communicative space for the heroes, similar to their reuniting forest. Within the lai, Tristan can exclaim in sudden first and second person:

'beautiful companion, and with us is true:

not you less me nor me less you.'

In this work exile is not insurmountable and communication is not final, whether it is letters carved in hazel, words echoed in a lai's verse, or any whisper in confidence in a forest.

Katharine Margot Toohey

Quemar Press

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Quemar Press' new Modern English translation of Bisclavret (Werewolf), Marie de France's medieval French Romance, is available here as a free download by clicking on the cover below.

Quemar Press' Preface:

Bisclavret is a re-imagining by Marie de France of traditional werewolf legends. This is a work where hierarchy between animals and humans can be demolished, and affection for an individual being (be it in an animal or human state) can be clear and unwavering.

‘At this sight, the king had great fear,

called all his companions here,

saying: “Lords, come before,

come here to watch this wonder;

how this animal bows to me,

with a man’s sense, calling for mercy.

For me, hunt those dogs back.

Watch he isn't struck.

This beast has understanding and reason.

Act now; light us on.

To the beast I grant rest,

for I'll hunt no more this forest.”’

In this lai's original text, the 'werewolf' has no monstrous or fearsome characteristics, but sleeps in his wolf form close by the king, who has a building affection for him. Here, the werewolf-knight is identical to an engaging and non-threatening wolf - similar to a wolf-cub. He is suspended in wolf-guise after his spouse had his clothes stolen to prevent him from turning into a knight again, leaving him forced to traverse the forest. There, the king is stunned at encountering this animal with a man’s reason and feels incapable of killing him in a hunt. He takes the wolf into shelter in the castle.

Marie de France, considered to be the earliest female French poet, constructed this lai from ancient Breton lais, originally translating them in the twelfth-century to Anglo-Norman French. While Quemar's Modern English translation is of all the original Anglo-Norman text, Marie de France's original Anglo-Norman is also included, juxtaposed with the translation. To reflect her tone, energy and structure, Quemar’s creative translation tries to preserve her four stresses to a line and suggest the couplet rhyme on the line’s end.

Marie de France also acts as the lai’s narrative voice, indicating levels of humour in the text and witty exaggerations, as when she recounts in jest the supposed consequences of the werewolf-knight’s wife’s nose being ‘nipped off’, apparently without any medical ill effects. When the king discovers that the spouse betrayed the werewolf-knight, she goes to live in exile with her new husband. Marie jests:

‘Together, they had many children.

Then these were well-known.

They had unusual features and appearance.

Many women in this lineage hence

were born without noses - honestly -

and continued to live nose-free.

The story you hear me tell

is true. Doubt nothing at all’

Sometimes in interpretations of this work, every action described within the narrative seems to be presented as serious. As that approach to the text could leave aspects of the it surreal or inexplicable, or erase aspects of Marie de France’s wit and narrative skill, Quemar Press’ translation attempts to retain the jocular as well as compassionate aspects of her voice.

An approach to the text that minimises jest might also risk minimising serious clarifying instances, which are made startling and intensified by their contrast with comedic elements.

In the original, Marie creates a remarkable level of clarity when the affection between the king and the werewolf-knight is unchanged by his form, affirming an underlying continuity of the self - regardless of state, regardless of situation.

Katharine Margot Toohey

Quemar Press

Bisclavret is a re-imagining by Marie de France of traditional werewolf legends. This is a work where hierarchy between animals and humans can be demolished, and affection for an individual being (be it in an animal or human state) can be clear and unwavering.

‘At this sight, the king had great fear,

called all his companions here,

saying: “Lords, come before,

come here to watch this wonder;

how this animal bows to me,

with a man’s sense, calling for mercy.

For me, hunt those dogs back.

Watch he isn't struck.

This beast has understanding and reason.

Act now; light us on.

To the beast I grant rest,

for I'll hunt no more this forest.”’

In this lai's original text, the 'werewolf' has no monstrous or fearsome characteristics, but sleeps in his wolf form close by the king, who has a building affection for him. Here, the werewolf-knight is identical to an engaging and non-threatening wolf - similar to a wolf-cub. He is suspended in wolf-guise after his spouse had his clothes stolen to prevent him from turning into a knight again, leaving him forced to traverse the forest. There, the king is stunned at encountering this animal with a man’s reason and feels incapable of killing him in a hunt. He takes the wolf into shelter in the castle.

Marie de France, considered to be the earliest female French poet, constructed this lai from ancient Breton lais, originally translating them in the twelfth-century to Anglo-Norman French. While Quemar's Modern English translation is of all the original Anglo-Norman text, Marie de France's original Anglo-Norman is also included, juxtaposed with the translation. To reflect her tone, energy and structure, Quemar’s creative translation tries to preserve her four stresses to a line and suggest the couplet rhyme on the line’s end.

Marie de France also acts as the lai’s narrative voice, indicating levels of humour in the text and witty exaggerations, as when she recounts in jest the supposed consequences of the werewolf-knight’s wife’s nose being ‘nipped off’, apparently without any medical ill effects. When the king discovers that the spouse betrayed the werewolf-knight, she goes to live in exile with her new husband. Marie jests:

‘Together, they had many children.

Then these were well-known.

They had unusual features and appearance.

Many women in this lineage hence

were born without noses - honestly -

and continued to live nose-free.

The story you hear me tell

is true. Doubt nothing at all’

Sometimes in interpretations of this work, every action described within the narrative seems to be presented as serious. As that approach to the text could leave aspects of the it surreal or inexplicable, or erase aspects of Marie de France’s wit and narrative skill, Quemar Press’ translation attempts to retain the jocular as well as compassionate aspects of her voice.

An approach to the text that minimises jest might also risk minimising serious clarifying instances, which are made startling and intensified by their contrast with comedic elements.

In the original, Marie creates a remarkable level of clarity when the affection between the king and the werewolf-knight is unchanged by his form, affirming an underlying continuity of the self - regardless of state, regardless of situation.

Katharine Margot Toohey

Quemar Press

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Quemar Press' new Modern English translation of The Beauty and the Beast (Parts One and Two of La Belle et la Bête) by Gabrielle-Suzanne de Villeneuve is available here as a free download by clicking on the cover below:

,Quemar Press' Preface

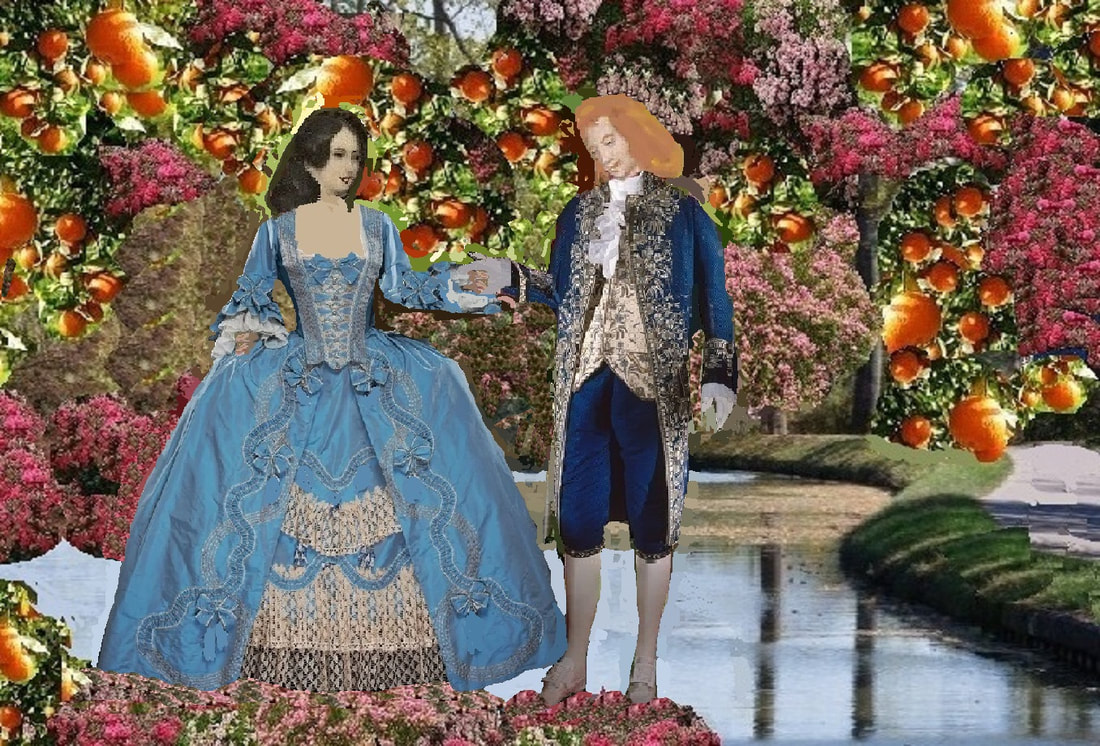

Villeneuve's extraordinary 18th-century French work, La Belle et la Bête, is underpinned by the idea of a female hero as she navigates things unknown to her, things kept from her, and shades of truth spoken to her in dreamscape. She has no other name or title but 'The Beauty', just as such attributes were included often in the titles of royalty. Raised as a Merchant's daughter, The Beauty's own royal heritage is not revealed to her until her adventure is concluding and she has achieved her goals. Initially, when her father is threatened by a Beast, she agrees to remain forever with it in its castle, in exchange for his life. Among the Castle’s enchantments for her, are dreams of an Unknown one, whom she loves and feels is also prisoner there. Exploring the layers of the castle and the layers of the realities and mysteries surrounding her, her character reaches new complexity and compassion as she feels growing affection for the Beast.

In later adaptions of this story, the Beast is often placed under an enchantment to give it an opportunity to remedy a lack of empathy. In Villeneuve’s original text, however, the Beast is placed in the Palace by enchantment without a remedial pretext. On one level, the Beast and The Beauty might be seen as co-existing as equal prisoners there, in contrast to later versions that are sometimes compared to the ‘Stockholm Syndrome’ (in which a captive confuses their identity with their captor, leading the captive to become fond and loyal to the captor).

Villeneuve’s work, however, does not focus on any reformation by the Beast. Instead, it casts light on the development of The Beauty’s character and empathy and how she achieves this. In dreams, an Unknown Lady (later identified as her aunt, a Good Fairy) advises and cheers her: ‘Courage, The Beauty: be the model for kind women: make yourself known to be as sage as you are charming'.

Here, the female hero is able to achieve this growth, and the castle and enchantments are centered on her to facilitate it. In watchful reflection and problem-solving, she progresses diligently, whether as a merchant’s daughter or newly-discovered royalty.

Villeneuve’s context and audience perhaps had royalist sympathies. At the time she wrote a large amount of her work, she had separated from her husband and was living with the Royal literary censor in Paris, evading prejudice about her protestant upbringing. Perhaps she not only created The Beauty as an ethical ‘model’, guide or example for society, but was also presenting a royal-centric society with a template portrayed as a bankrupt merchant’s daughter until the end of the initial narrative.

Book Two concludes with the Beast beginning to tell The Beauty his history, in the forever ongoing discourse between them. While this edition concentrates on the immediate narrative of The Beauty and the Beast, after the conclusion of Parts One and Two of La Belle et la Bête, uniting The Beauty and the Beast, Villeneuve’s text began two new, different sections, as told by the Beast and the Fairy. Among these new narratives, she alludes to the circumstances that led to The Beauty and the Beast’s story.

She explains that The Beauty is the child a of a marriage between a Fairy and a King. In Fairy prejudice against this partnership, The Beauty was stolen away but rescued by the Good Fairy and exchanged for a dead merchant’s child. At The Beauty’s birth, the Good Fairy had destined her to marry the Prince. His mother had gone to war and left him as a child in the care of a Bad Fairy, who later transformed him into a Beast in revenge for her unrequited passion for him. In light of this, the Good Fairy placed him in the castle, knowing The Beauty’s shrewdness and sympathy would eventually lift the enchantment.

Villeneuve adds that The Beauty married the Prince, with her merchant family living by her in her Court and her Sisters there reuniting affectionately with their distanced fiancés. Unlike later adaptions of the story, in Villeneuve’s text The Beauty’s sisters are never subjected to retribution for their feelings of rivalry. Similarly, neither The Beauty or the Prince have animosity towards the enchanted palace that kept them captive. Instead, they return often to visit the sentient spirits of place there (who manifested for them as monkeys, parrots and songbirds).

Both The Beauty and the Prince have been subject to enchantment, as a circumstance that has happened to them.‘The model for kind women’, The Beauty and her actions, however, have her own agency, unpossessed by any charm in any castle or any society.

‘But The Beauty without agitating herself, and with a gentle, assured voice said to it, “Good evening, The Beast.” “Do you come here voluntarily,” continued the Beast… The Beauty responded that she had not had any other intentions.’

Katharine Margot Toohey

Quemar Press

Villeneuve's extraordinary 18th-century French work, La Belle et la Bête, is underpinned by the idea of a female hero as she navigates things unknown to her, things kept from her, and shades of truth spoken to her in dreamscape. She has no other name or title but 'The Beauty', just as such attributes were included often in the titles of royalty. Raised as a Merchant's daughter, The Beauty's own royal heritage is not revealed to her until her adventure is concluding and she has achieved her goals. Initially, when her father is threatened by a Beast, she agrees to remain forever with it in its castle, in exchange for his life. Among the Castle’s enchantments for her, are dreams of an Unknown one, whom she loves and feels is also prisoner there. Exploring the layers of the castle and the layers of the realities and mysteries surrounding her, her character reaches new complexity and compassion as she feels growing affection for the Beast.

In later adaptions of this story, the Beast is often placed under an enchantment to give it an opportunity to remedy a lack of empathy. In Villeneuve’s original text, however, the Beast is placed in the Palace by enchantment without a remedial pretext. On one level, the Beast and The Beauty might be seen as co-existing as equal prisoners there, in contrast to later versions that are sometimes compared to the ‘Stockholm Syndrome’ (in which a captive confuses their identity with their captor, leading the captive to become fond and loyal to the captor).

Villeneuve’s work, however, does not focus on any reformation by the Beast. Instead, it casts light on the development of The Beauty’s character and empathy and how she achieves this. In dreams, an Unknown Lady (later identified as her aunt, a Good Fairy) advises and cheers her: ‘Courage, The Beauty: be the model for kind women: make yourself known to be as sage as you are charming'.

Here, the female hero is able to achieve this growth, and the castle and enchantments are centered on her to facilitate it. In watchful reflection and problem-solving, she progresses diligently, whether as a merchant’s daughter or newly-discovered royalty.